Description

MEXICAN CONSULAR ID CARDS

For the estimated 8.5 million undocumented immigrants living in the United States, day-to-day life has always been precarious. Not only do they not have the legal right to live and work in America, but many cannot prove their own identity. Lack of identification prevents undocumented immigrants from accessing the few public and private services that are available to them and intensifies their fear of contact with police and other official institutions. The events of September 11 and the scrutiny of undocumented immigrants that followed deepened this anxiety. In this light, many of the estimated 4.7 million Mexicans living in the U.S. without authorization turned to a little-known Mexican government identity document called the matrícula consular. The Mexican Consular ID Cards have given undocumented immigrants a sense of security but have been received with mixed reactions by public and private institutions.

A sharp debate on the merits of Mexican Consular ID Cards has engaged the public, political circles, the media, the private sector, immigration authorities, and law enforcement agencies. On the one hand, proponents of such programs say the cards protect immigrants, their families, and communities by facilitating their ability to open bank accounts, access some limited public services, and work with authorities to resolve crimes and other social ills. On the other hand, critics question whether undocumented immigrants should have access to such services, and assert that Mexican Consular ID Cards programs subvert U.S. policy and promote unauthorized immigration.

How this debate shapes up is likely to have significant consequences for millions of undocumented immigrants. It is also likely to have a bearing on how the United States shapes its domestic security efforts. Understanding the debate requires examining several key aspects of the Mexican Consular ID Cards programs, including the extensive Mexican program, the cards’ relationship to immigrant banking and remittances, the effect on local law enforcement, and the prospects for developing such programs for other countries.

Mexico’s Vast ID Program

Mexican consulates have issued the matrícula consular, also know as the matrícula, to Mexican citizens living abroad for 131 years. The Mexican Consular ID Cards is a way for the Mexican government to keep track of its citizens for consular and tax purposes, collect data on them, and provide them with what the government considers to be a basic human right: the ability to identify oneself.

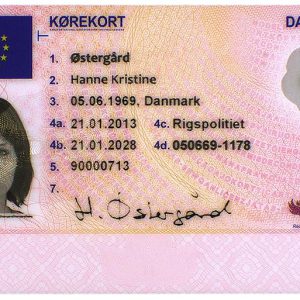

Security of Mexico’s Matrícula Consular

The matrícula consular is available to any Mexican citizen living abroad. Applications for the matrícula must be submitted in person to consular officials. The applicant must present a Mexican birth certificate accompanied by a photo ID issued by a Mexican government authority, such as a voter registration card, passport, military service card, or expired matrícula. If the applicant cannot provide these documents, the consulate confirms the applicant’s identity by investigating his or her background through authorities in Mexico. Additionally, the applicant must provide some proof of their address in the U.S., usually a utility bill, and that address must be within the consular district of the consulate issuing the card. The information, card number, and a digital photo of the applicant are recorded by the consulate and sent to a central registry in Mexico.

Critics say that the documents used to verify identity and citizenship when the cards are issued can be falsified. They cite a case in which a Mexican arrested on immigration violations was found with three matrícula cards in different names. They also argue that it would be possible for a national of another country to obtain a matrícula by fraud.

Proponents suggest that the matrículas are comparable, in terms of security, to U.S. state-issued driver licenses. Sophisticated tamper-proof holograms make the cards extremely difficult to forge or modify. Soon, say supporters, the matrículas will have a security feature that driver licenses do not: Mexico is creating a computer network that will give all consulates instant access to information on cardholders.

The cards identify the holder, certify that he or she is a Mexican citizen, and give his or her birthplace and U.S. address. They cost about $29 each and are valid for five years. The cards are issued without regard to immigration status and give no immigration information. Mexicans in the U.S. legally can and do use the matrícula, particularly when returning to Mexico, but it is most useful to the undocumented because they are less likely to have passports, green cards, or other forms of identification.

While the matrículas are not new, a combination of factors converged in late 2001 and early 2002 to make the matrícula explode in popularity. First, anxiety over identification following September 11 prompted Mexicans to apply for the card in droves. In response to that anxiety and demand, the Mexican government began to market the cards through its network of 47 consulates in the U.S., and set up “mobile consulates” to issue the matrícula in communities without a consulate. The intense outreach proved effective. In 2002, Mexico issued over 1.4 million of the cards in the U.S. alone, compared to the 664,000 it issued worldwide in 2001.

In addition, the Mexican government rolled out novel strategies to make the matrículas more useful to cardholders. Beginning in early 2002, Mexico enhanced the security provisions of the matrícula and the process used to issue it. It also conducted a well-organized campaign to educate U.S. banks, police departments, and governments about the new features and encourage them to accept the matrícula as a valid form of identification. The campaign targeted two fundamental needs of undocumented Mexican immigrants: the ability to identify oneself to local law enforcement and the ability to access financial services in order to save and remit money.

Banking and Remittances

Even before September 11, lack of identification posed a problem for undocumented immigrants who wanted to open a bank account or send money home. Some 43 percent of Latinos in the U.S. do not have bank accounts, and a far larger proportion of undocumented Mexican immigrants do not have bank accounts. Lack of identification is one of several reasons why undocumented immigrants do not use banks. Shut out of the formal financial system, undocumented immigrants tend to cash paychecks at expensive check-cashing shops, save their earnings in cash, and use either unreliable informal networks or costly wire-transfer services to send money home. This makes them targets for robbery and home invasion, subjects them to high transaction costs, and represents unused financial capital.

The money sent home by Mexicans working abroad equals at least 1.1 percent of Mexico’s GDP, so the banking issue is important to Mexico’s domestic economy as well as the welfare of its citizens abroad. In the past two years, the matrícula has helped Mexicans satisfy the documentation requirements of U.S. banks and given those banks a new market. At last count, over 70 banks and 56 credit unions accepted the matrícula as one of the two forms of identification usually required for opening an account. These banks include giants such as Citibank, Bank of America, U.S. Bancorp, and Wells Fargo. Wells Fargo estimates that it has used the matrícula to open over 70,000 new accounts since it began accepting the card in November 2001.

Public policy by both the Mexican and U.S. government played a significant role in the acceptance of the matrícula by mainstream financial institutions. The Mexican government gave the card security features strong enough to satisfy U.S. banks and actively promoted the new card to the major institutions in the sector. In July 2002, the U.S. Treasury Department issued guidance to banks explicitly stating that the “know your customer” requirements of one of the new pieces of domestic security legislation, the USA Patriot Act, did not prohibit banks from using the matrícula as one way to verify identification. However, it stopped short of endorsing use of the card.

Local Law Enforcement

Local U.S. police and sheriff departments have been among the most enthusiastic backers of the consular IDs. Nationwide, an estimated 800 departments accept the matrícula as valid identification. Many cities have also received the scanners that allow officers to check the cards’ most sophisticated security features.

Police departments welcome the cards for the following reasons:

•By facilitating the use of banks, the cards help immigrants avoid carrying or stockpiling large amounts of cash, which makes them targets for robbery and home invasions. In some cases, the police themselves have asked local banks to accept the matrícula.

•Having identification encourages people to report crimes and to come forward as witnesses. It also allows police to keep better records.

•When the police stop someone without identification on a minor charge, they are forced to hold them overnight when a citation would otherwise suffice. Resources are also wasted in identifying detained undocumented immigrants.

•People without identification are more likely to flee when stopped by police.

•The matrículas make it easier to identify dead or unconscious people.

•Local police are generally not responsible for immigration enforcement, so immigration status is irrelevant for their purposes.

Other Impacts of the Matrícula

There are several other realms in which the impact of Mexican Consular ID Cards have begun to be felt.

Direct uses of the cards lie in the very narrow band of public and private services for which high-quality identification is required, but proof of legal residency is not. Private companies have begun to accept the matrícula for opening accounts for utilities and insurance. USAir and Aeromexico, among other airlines, allow passengers to use the matrícula to board flights originating in the U.S..

The local governments of 80 cities, including Tucson, Phoenix, Denver, Los Angeles, San Antonio, San Francisco, Chicago, Houston, and Dallas accept the matrícula for uses such as obtaining a library card, entering public buildings, obtaining business licenses, registering children for school, and accessing a few, limited public services. At the state level, the most important use of the matrículas is in obtaining driver licenses. Although most states now require proof of legal immigration status, there are about 13 states that do accept the matrícula as proof of identity when issuing a license.

The acceptance of matrículas has not, however, been uniform. In both Arizona and Colorado, at least one house of the state legislature has passed legislation banning use of the matrícula by state and local governments.

At the federal level, public policy has been mixed. Most federal programs require proof of legal residency, so the impact of the matrícula has been minimal. A pilot program to accept the matrícula for entry to a federal courthouse was scrapped under political pressure. The Department of Homeland Security has not made decisions explicitly involving the matrícula. The Transportation Safety Administration, for example, lets airlines set their own criteria for acceptable identification for passenger check-in. In the U.S. Congress, a bill has been introduced that would formally endorse use of the matrícula for banking, as well as one that would bar federal agencies from accepting any foreign-issued ID other than a passport.

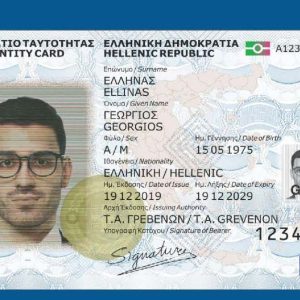

Countries Following Suit

Other nations are now trying to follow Mexico’s example. Guatemalan consulates recently began issuing a similar card, which is now accepted by several banks. Peru plans to begin a pilot program within the next two months. Honduras, El Salvador, and Poland are also said to be planning consular ID card programs. No other country has yet matched Mexico’s political and logistical support of such programs, but they may find that Mexico’s success has blazed a trail for them both with U.S. governments and businesses and in raising awareness among immigrants.

It is important to note, however, that consular identification programs are not new. Guatemala, for example, has long issued passports to its citizens living abroad without regard to their immigration status. Since 1999, these passports have been roughly as secure as the Mexican matrículas currently are, and contain all of the same information except for a U.S. address. Requirements for obtaining the passports are no more stringent than for the ID cards. A number of other countries also issue passports through their consulates.

The popularity of consular IDs could raise new difficulties. If a large number of countries issue such cards, the process of verifying their authenticity might become confusing and costly. If other countries introduce less secure consular IDs, they could be confused with more secure documents like the Mexican matrícula, with the effect of either compromising security or degrading confidence in the better IDs.

Public perceptions of particular countries could also play a role in U.S. acceptance of further consular ID programs. While the Mexican consular IDs have raised relatively little concern with voters, if a country such as Pakistan issued an equally secure ID card, it might provoke a different reaction. Each of these hypothetical situations demonstrates the need for well-guided and coherent public policy on the issue.

Areas for Future Research

Both consular ID cards and the new emphasis on identification as a security measure are relatively new public policy issues. Policymakers are now seeking answers to a range of questions, including:

• How secure are the matrículas and other consular ID cards compared to state-issued drivers licenses, passports, and other forms of identification? How useful is identification in general as a security tool?

• As consular IDs flourish, do the U.S., immigrant-sending countries, or individual states have an interest in setting security standards for the IDs? More stringent security measures, particularly in issuing the IDs, will boost the confidence of U.S. officials, but make it harder for immigrants from poor and rural areas to get identification.

•What services can consular IDs currently be used to access? Use of the matrícula outside of law enforcement and banking has not been well documented. The services available to undocumented immigrants and identification requirements vary across state and local jurisdictions. Although this issue ties into the ongoing debate over what rights and privileges undocumented immigrants should have, a realistic assessment of the fiscal costs and social benefits of accepting the matrículas could inform debate.

•For what uses should consular IDs be accepted and why? What are the real benefits and risks in each case? Using the IDs for local law enforcement purposes may not have an obvious downside, but for other uses, such as boarding airplanes or entering federal buildings, this is not entirely clear.

•What are “best practices” for other countries launching consular identification programs? Mexico’s experience with the matrícula is a potential model, but other innovations are available for consideration. For example, the Philippines gives its workers going abroad an ID card that doubles as an ATM card, in order to encourage them to save and remit.

Conclusion

The impact of consular ID cards in the United States, while far-reaching, is still unclear. Opponents of the programs argue that, by granting undocumented immigrants increased access to institutions and services, they permit undocumented immigrants to take a step toward de facto regularization. They also express concern that the cards and the process for issuing them are not sufficiently secure and could be abused by criminal or terrorist elements.

Supporters of consular ID programs counter that acceptance of the card promotes law and order by encouraging undocumented immigrants to assist police and use formal financial channels. They also argue that state-issued driver’s licenses are equally imperfect security tools and point out that the consular ID cards in no way affect enforcement of U.S. immigration law. Ultimately, say proponents, denying the use of the matrícula does nothing to discourage unwanted immigration and only serves to further marginalize a class of people who contribute greatly to the American economy.

Many on both sides see the cards as a symptom of inconsistent immigration policies, but disagree on the solution. For critics, the cards demonstrate the need for strict enforcement of immigration laws; for proponents, the problem is the absence of sufficient legal migration channels.

The debate over consular IDs continues, affecting a broad spectrum of U.S. policy. Federal, state, and local governments all have a stake in the outcome, as do the private sector, foreign governments, and the public. Most affected of all could be millions of undocumented immigrants, who will see their fortunes affected by the fate of consular ID programs.

Sources

Bair, Sheila. 2003. Statement before the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Hearings on Matrícula Consular. Washington, March 26.

Dinerstein, Marti. 2003. IDs for Illegals. Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, Washington: CIS.

Embassy of Mexico in the United States and the Mexican Consulate in Washington, D.C.

Passels, Jeffrey. 2002. “New Estimates of the Undocumented Population in the United States.” Migration Information Source.

Suro, Robert, Sergio Bendixen, B. Lindsay Lowell, and Dulce C. Benavides. 2002. Billions in Motion: Latino Immigrants, Remittances and Banking. Washington: Pew Hispanic Center.

United Nations. 2002. International Migration Report: 2002.